The unlawful murder of Houston-native George Floyd in May 2020 sparked a series of protests across the U.S. and globally. One year later, the former police officer, Derek Chauvin, was convicted of the murder of Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Despite the seeming progression in convicting one police officer for the case of police brutality against a person of color (POC), recent deaths of fellow Black Americans – including Dante Wright, Ma’Khia Bryant, Andrew Brown Jr. – across the United States have left many American citizens questioning their trust and faith in law enforcement and the Justice Department.

Police brutality is not a new concept in the United States. Americans of all races, ethnicities, ages, classes, and genders have been subjected to police brutality throughout U.S. history; however, the great majority of victims have been Black people and POC. Current policing strategies are inherently and overtly racist since the inception of this country. Dating to the 13th amendment in 1865, which abolished slavery in the U.S., Jim Crow laws worked to control and legalize racial segregation. Those who were ‘defiant’ of these statutes faced arrests, fines, and imprisonment, and police would often resort to violence and death. Today, police brutality is a civil rights violation due to the extreme form of excessive and unwarranted use of force and violence by law enforcement. Yet, fatal shootings by on-duty police officers in the United States are a norm in recent years. Could this be a result of intergenerational prejudices and racism towards those who have been historically oppressed or marginalized within police departments across the nation? It begs people to question why there has been no reform on policing strategies and tactics.

2014 saw the killing of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old unarmed Black man, by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson. The tragic event turned the eyes of Americans everywhere for the first time, igniting unrest and prompting demonstrations across the nation. In turn, the Washington Post began to log every fatal shooting at the hands of on-duty U.S. police officers since 2015, gathering data primarily from news accounts, social media, and police reports. According to the Post’s data, the rate at which shootings occur remains at a steady number of nearly 1,000 killings annually. From this share of fatal shootings, Black Americans are killed at more than twice the rate than white Americans despite accounting for less than 13% of the U.S. population. In 2021 alone, there have already been 292 deaths from police shootings.

Frank Edwards, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito conducted a study in 2019 on the “Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex.” To measure the risk of being killed due to police force in the United States across various social groups, data was collected on police-involved deaths. Additionally, the study includes estimates of the proportion of all deaths accounted for by police use of force. It was found that police from the United States kill at a much higher rate than in other advanced democracies in which race, sex, and age play a major role in exposure to the criminal justice system.

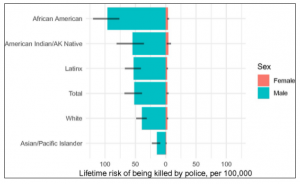

Figure 1. Lifetime Risk of Being Killed by Police (2013-18 data)

Figure 2. Prison Policy Initiative: U.S. Police Killings vs. Other Countries

Figure 1 displays the data collected from the authors, providing information on estimates related to lifetime risk of being killed by police. Findings saw that Black men faced the highest risk of being killed by police at about a 1 in 1,000 chance over the life course. Furthermore, The average lifetime odds of being killed by police are about 1 in 2,000 for men and about 1 in 33,000 for women. Risk peaks between the ages of 20 and 35 years old for all groups. For young men of color, police use of force is among the leading causes of death. Additionally, the Prison Police Initiative compiled data from the United States, the Netherlands, England, Wales, Iceland from 2019; Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Germany, and Norway from 2018; and Canada from 2017 in which Figure 2 displays the annual rates of police killings in each country in comparison to the U.S., accounting for differences in population size. From Figure 2, it is evident that the current policies and practices of the U.S. enable and may even encourage police violence.

The Black Lives Matter movement has brought the issues of police violence and deep-rooted racial inequities in America to the forefront of national and local issues. With every additional unjust killing of people of color, it is imperative that the United States enacts change within Police Departments. A 2016 survey from the Police Executive Research Forum found that agencies spent a median of 58 hours on training for new recruits on how to use a gun and 49 hours on defensive tactics. However, time spent on de-escalation and crisis intervention was only about eight hours worth of training. Changing the culture of excessive police force must happen at the source as well as major federal legislation for police reform. Federal law, for instance, must enact change as the Supreme Court has given police plenty of leeway to use police force. The case Graham v. Connor from1989 held that officers could use force if doing so was “objectively reasonable.” Still in place today, the Supreme Court’s standard allows for various situations that should never develop in the first place. However, not all hope is lost. Across the nation, state and local governments have undergone change within their police departments. As an example, the legislators in California introduced a bill to ban chokeholds. In New York, the law that kept secret the disciplinary records of police officers was finally repealed on July 12th.

References

“Fatal Force: Police Shootings Database.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 22 Jan. 2020,

www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/.

Frank Edwards, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito. “Risk of being killed by police use of force

in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex.” Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, Aug. 2019, 116 (34) 16793-16798; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1821204116

Leonard Moore. “Police brutality in the United States”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 27 Jul. 2020,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Police-Brutality-in-the-United-States-2064580.

Taryn A. Merkl. “Protecting Against Police Brutality and Official Misconduct.” Brennan Center

for Justice, 29 April 2021,

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/protecting-against-police-brutal

ity-and-official-misconduct.