Ethical and Cultural Considerations in Dengue Surveillance and Prevention

By: Emily Clark

Dengue surveillance and prevention should be contextualized to community needs and abilities, with an unwavering commitment to justice for the benevolence of individuals who are most at risk of developing disease.

Dengue is a disease spread by day-biting mosquitoes. It has a high prevalence rate and no therapeutic drug or vaccine available. It was estimated in 2013 there were a total of 58.40 million symptomatic dengue infections and 13,586 were fatal worldwide. If an individual is infected with Dengue, they can experience a spectrum of symptoms: some are asymptomatic, meaning the individual is infected with a virus but does not get sick with the disease; others could develop a fatal hemorrhagic disease called Dengue Shock Syndrome. There are four different strains of the virus which puts individuals living in endemic areas at risk of developing the disease four unique times. Once an individual is infected with the virus, they are immune to that specific strain but not the others. However, each new infection leads to increased severity of disease.

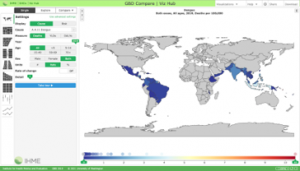

Certain regions of the world carry a higher burden of Dengue. Conditions that facilitate the spread of this disease are urbanization and concurrent population growth, substandard housing, inadequate water, sewage and waste management systems. The image was created by IHME highlights countries where Dengue is endemic.

Though Dengue is present in a variety of regions, this case study examines Dengue in the context of Chetla, a high-risk area on the south side of Kolkata, India. In Chetla, a group of researchers conducted a survey that aimed to “assess the community perceptions and risk reduction practices toward prevention and control of malaria and dengue at slums of Chetla in south Kolkata and to explore the perspectives of relevant local stakeholders” (Podder et al. 2019, p.1).

The authors conclude that increased social behavior change and community engagement is needed to combat Dengue in this community. The author recommends contextualizing interventions, focusing on community needs and addressing current barriers. A few of the barriers found in this example were lack of community awareness, poor infrastructure in slums, proximity to a canal (water source), and unavailability of specific medicines. It is important to scale community programs to build trust among communities and researchers. This could also be a means to build surveillance systems and further education about the disease.

Additionally, limited resources and inadequate surveillance leave communities burdened with a crisis mentality. This crisis mentality does not create opportunities for prevention, but rather forces groups to react to the epidemics once numerous severe cases are detected. I would also argue that the crisis mentality has created the ethical dilemma present in vaccine development for Dengue. There is one known vaccine for Dengue, but it is widely rejected on ethical principles, especially after it was administered in the Philippines in 2016. The ethical argument for this vaccine is that individuals who had prior exposure to Dengue benefit from the vaccine, but those who have never been exposed experience serious illness as a result. Further explanation of the situation can be found here.

In addition to initial reactions to a vaccine, we must consider the past and future implications each action may have. This is relevant in our current COVID-19 vaccine campaign even though there are no known harmful effects of the COVID-19 vaccine (aside from a few allergic reactions). Understanding how campaigns have been harmful in the past helps us to be more empathetic as to why some people might be fearful of a vaccine, while serving as a reminder to the public health community to operate with integrity and sound ethical reasoning because no public health program exists in isolation.

References

Bhatt, S., Gething, P., Brady, O. et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496, 504–507 (2013). https://doi-org.proxygw.wrlc.org/10.1038/nature12060

Gubler, D. J., & Clark, G. G. (1995). Dengue/Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: The Emergence of a Global Health Problem. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 1(2), 55-57. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid0102.950204.

Iamat.org2020. India:Dengue | IAMAT. [online] Available at: https://www.iamat.org/country/india/risk/dengue#

Podder, P. (2019). Community perception and risk reduction practices toward malaria and dengue: A mixed-method study in slums of Chetla, Kolkata. Indian Journal of Public Health, 63(3), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_321_19

Rosenbaum, L. (2018). Trolleyology and the Dengue Vaccine Dilemma. The New England

Journal of Medicine, 379(4), 305–307. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1804094

Shepard DS, Undurraga EA, Halasa YA, Stanaway JD. The global economic burden of dengue: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016 Apr 15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00146-8.

The cover art for this article was created by Urooj Ali.